COP27: Outcomes from the climate talks and what it means for action in Scotland

Mary Church who attended the UN climate conference COP27 in Egypt reflects on the outcomes from the talks.

As the first UN climate summit in the Global South for 6 years, COP27 was billed as ‘the Implementation COP’, where rhetoric would be turned into action, particularly in terms of support for countries on the frontlines of the crisis.

While the summit in Sharm El-Sheikh did not deliver on these expectations, to say nothing of what is needed to stop complete climate breakdown, it did secure some important wins. Not least a Loss and Damage Fund, and a renewed emphasis on equity, both of which were resisted to the bitter end by the rich historical polluters who continue to evade their responsibility for causing the crisis.

However, many issues are still to be decided, including vital long term finance commitments and the dangerous question of whether so-called emissions removals and avoidance would be allowed to be traded in Paris Agreement carbon markets. Staggering hypocrisy was on display from Global North countries who pitted calls for urgently needed Loss and Damage finance against meeting the critical 1.5°C target, and fossil fuel phase out.

Meanwhile negotiations were played out against a highly-charged campaign to free political prisoners of Egypt’s brutally repressive regime.

As the dust settles on this year’s summit, this blog outlines the key outcomes of COP27 and points to what next for the climate movement here in Scotland.

Progress on Loss and Damage

With extreme weather events wreaking havoc around the world all too frequently, Global South countries made finance for Loss and Damage, or the now unavoidable impacts of climate change, a top priority at COP27. Their goal to establish a finance facility for Loss and Damage at COP27 was ultimately won, despite the best efforts of Global North countries to split the main negotiating bloc representing Global South interests.

Northern countries, the USA and Germany in particular, came to COP27 pushing a deeply inadequate approach to Loss and Damage finance centering insurance schemes. In a last ditch attempt to divide and conquer the EU pulled a proposal out of the bag for a fund that would be open to fewer countries. Ultimately this was rejected, but the final text leaves open the contentious question of where funds will be sourced and therefore the very real possibility that it will remain empty.

Announcements of Loss and Damage funding by Global North countries during COP27 attracted a lot of attention and gave the impression of good faith on this intractable issue. However analysis shows that most of the pledges are simply repackaging of existing climate finance commitments and are directed towards the Global Shield insurance scheme championed by Germany, or technical support, rather than badly needed public funding in response to both disasters and slow onset loss and damage.

This has led to accusations of ‘Loss and Damage washing’. Even Scotland’s £5m contribution was a repackaging of an existing commitment, though importantly, it is grant based.

A massive civil society campaign, supported by First Minister Nicola Sturgeon’s championing of the case for climate reparations, helped secure this historic win. Now the focus must now be on securing new and additional, grant-based finance for the fund, that goes beyond symbolic sums and meets the very real need of climate impacted countries.

Climate finance

Loss and Damage funding is only one of a number of strands of the UN climate negotiations relating to finance. Under the Climate Convention, rich historical polluters are required to provide funding, and other forms of support, to Global South countries in both cutting emissions and adapting to the impacts of climate change.

At the Copenhagen summit in 2009 rich countries promised to provide $100bn per year by 2020. The goal was extended to 2025 and has been repeatedly missed, with analysis from Oxfam estimating that the real value of the $83.3bn rich countries claim to have delivered toward that goal in 2020 is actually around a third of that sum.

A new long term goal for climate finance is one of the key issues under negotiation in the UNFCCC, with Global South countries calling for lessons to be learned from the failure to meet existing commitments, and for a new goal to be based on what is needed and owed, rather than a convenient figure plucked out of the air (like the Copenhagen commitment was).

Decisions on the new goal are scheduled for COP28, but usefully the Sharm El-Sheikh Implementation Plan highlights that the needs of Global South countries in the period up to 2030 are estimated at $5.8-5.9tn.

Analysis of the UK’s historical responsibility for climate pollution estimates the UK’s fair share of climate finance to be in the region of £1 trillion, if emissions were reduced to zero by 2030. Scotland’s fair share would be a proportion of that sum. Given that we are not on track even to meet our much longer term goals of net zero by 2050 (UK) and 2045 (Scotland), we owe substantially more. The Scottish Government must go beyond symbolic sums based on what could be found down the back of the sofa and commit to paying its climate debt, maximising the use of its existing fiscal levers and exploring new and innovative sources of finance, to fulfil this.

‘Keeping 1.5°C alive’

Bringing down the global emissions driving the climate crisis – mitigation – is always high on the agenda at the UN climate talks. In theory anyway. Because despite 26 years of such negotiations emissions are still rising and despite all the hype around ‘keeping 1.5°C alive’ at the Glasgow summit the world is on course for a hellish 2.8°C or more.

The next official round of ‘Nationally Determined Contributions’ (NDCs), as Paris Agreement pledges are officially called, are not due until 2030 – far too late to stop climate breakdown. In recognition of this, countries were asked to voluntarily update their pledges to cut emissions ahead of COP27. Updated pledges reduce emissions at 2030 by only 1%, and despite leading this call as outgoing president of COP26, the UK Government failed to increase its own commitments.

Global North countries, particularly the UK, seemed to adopt the goal of ‘keeping 1.5°C alive’ at COP27 with a previously unseen zeal. Unfortunately, this was little more than a cynical manoeuvre to play the 1.5°C target off against Loss and Damage finance, and make it look like Global South countries were blocking on ambitious emissions reductions. Global South countries’ – whose per capita and historic emissions are a tiny fraction of those of Global North countries – Paris Agreement pledges for deep reductions are partially contingent on finance and support from Global North countries. Yet as outlined above, existing inadequate commitments remain unfulfilled.

Rich historical polluters are gambling with the highest stakes imaginable in running down the clock on 1.5°C: by failing to cut their own emissions in line with their obligations, and failing to deliver their financial obligations, they are shifting the responsibility onto the shoulders of countries who have done the least to cause the problem and are on the frontlines of impacts. With 3 of the last 4 years of climate targets missed, Scotland is no different. A new Energy Strategy is due imminently and a review of the Climate Change Plan next year: these frameworks must deliver a transformation of our economy away from fossil fuels.

Fossil fuel phase out

Having been scapegoated in the media at last year’s summit for apparently watering down language on coal phase out at COP26, India initiated a call for language to be included on the ‘equitable phase down all fossil fuels’. The word equitable here is key, as it puts the onus on rich, historical polluters to move first and faster.

The issue generated significant attention during the last days of the summit, with some unlikely champions of fossil fuel phase out essentially using the issue in an effort to derail the negotiations and avoid being held to Loss and Damage finance.

The strategy failed – the fund was agreed – the result being that on fossil fuels the Sharm El-Sheikh Implementation Plan simply repeats the text from last year’s Glasgow Climate Pact on the ‘phase down of unabated coal’. This lets Global North countries who tend to be less reliant on coal off the hook, and is seriously tempered by the massive loophole that ‘unabated’ brings by giving a blessing to coal projects that are ‘carbon capture and storage ready’.

In their speeches to the closing plenary of COP27, those unlikely champions of fossil fuel phase out – the UK, US and EU – devoted substantial time to ‘calling out’ the lack of progress in the text on this front, despite their own fossil fuel expansion plans. Let’s be clear: there is nothing to stop countries from phasing out fossil fuels, a UN mandate is not necessary. This staggering hypocrisy must be called out and utilised in campaigns at home to fight new fossil fuel infrastructure.

COP26 President Alok Sharma’s table-thumping on fossil fuel phase out must be translated into the UK Government overturning its plans for North Sea oil and gas expansion, saying no to the Rosebank field and rejecting the new coal mine planned in Cumbria.

Here in Scotland, the First Minister can show real climate leadership by saying no to plans for a new gas power plant at Peterhead, and committing to an end date for fossil fuels in the energy system, within the decade, in the Scottish Government’s forthcoming energy strategy.

Just Transition

Just Transition first appeared in the UN climate regime in a brief sentence in the preamble of the Paris Agreement, as a result of many years of hard work by the international trade union movement. The concept was initially seen by Global South countries as lacking in content to make it relevant to their contexts. Again, questions of equity come in here, for example how to talk about a just transition for workers affected by energy transition without also addressing the urgent need for access to energy for the 2billion people worldwide without.

The Sharm El-Sheikh Implementation Plan therefore represents something of a breakthrough with the establishment of a work programme on Just Transition focused on pathways to meeting the Paris Agreement goals, firmly situated in the context of equity and the ‘common but differentiated responsibility’ between rich historical polluters and those on the frontlines of the crisis.

It’s vital that we bring global justice perspectives into our work on just transition here in Scotland – an energy transition that is too slow or fails to take account of the impact of extractivism in the Global South for resources needed for renewables – is ultimately not a just transition. That’s why it’s crucial that plans for a more circular economy in Scotland set consumption targets, and the new Energy Strategy takes account of material demands.

Carbon markets

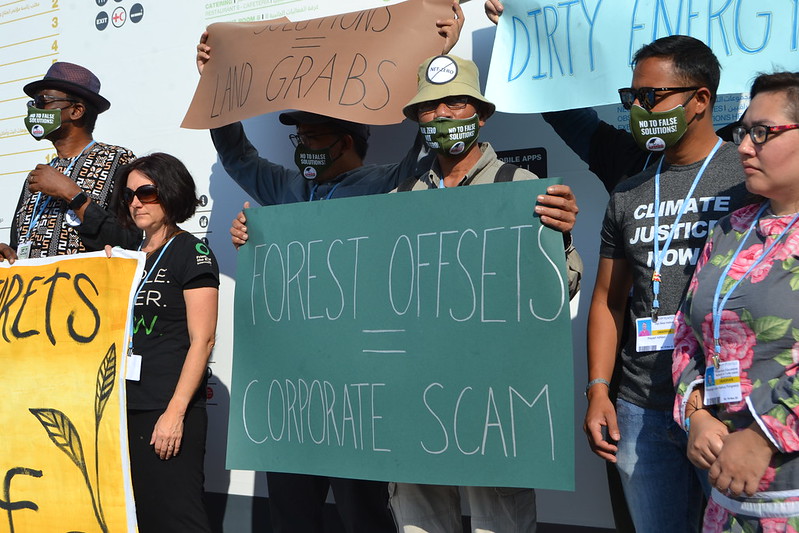

Carbon markets allow polluters to continue emitting greenhouse gases, for a price, either through trading or offsetting (paying someone else to cut their emissions). At the Glasgow COP26 summit governments pushed through an agreement on carbon markets under the Paris Agreement – something Friends of the Earth International has been fighting against for many years.

Carbon markets are a dangerous distraction that give the impression of action but have done nothing to reduce emissions over the past 20 years. With no top-down, science or justice based targets in the Paris Agreement carbon markets are simply unworkable and a major distraction from real solutions to cutting emissions. They are also linked to the scam of offsetting and human rights abuses which often accompany it.

COP27 was set to agree details of whether emissions avoidance and removals schemes would be allowed into Paris Agreement carbon markets, however the decision was delayed to future summits. Emissions avoidance is where carbon credits are awarded for theoretical emissions reductions from an activity that was stopped from happening – i.e. a forest that was not felled, or a coal power plant that was not built – a system that is wide open to abuse.

Emissions removals schemes put forward in a report to COP27 range from human rights trashing land-based projects such as plantations, to unreliable unproven-at-scale carbon capture schemes, to the engineering of weather through for example a truly terrifying concept called solar radiation management.

The extremes to which governments appear prepared to go to avoid taking the action that science tells us is needed to turn the crisis around – phasing out fossil fuels – is deeply disturbing. It is tempting to look away, but we must not sleepwalk into the dystopian future of climate apartheid and uncontrollable experiments with nature that these false solutions to the climate crisis would bring. In Scotland this means fighting plans for a new ‘carbon capture and storage ready’ gas power plant at Peterhead, and preventing the opening up of our land and nature for sale on international carbon markets.

Human rights

Held against the backdrop of shrinking civil society space globally, COP27 saw an intense focus on the Egyptian Government’s highly repressive regime that has arbitrarily detained and tortured thousands.

Climate justice groups were resolute in our solidarity with Egyptian prisoners of conscience including high profile hunger striker, British citizen Alaa Abd El-Fattah, the rallying cry of movements at COP27 – ‘we will never be defeated’ – adapted from the title of his book. It was devastating to leave the summit with Alaa still in jail, the UK Government having failed to prioritise securing his release.

Alaa, and so many others, remain in a highly precarious situation. The spotlight must not be allowed to move on now that COP27 is over. There can be no climate justice without human rights, and we must continue to stand in solidarity with Alaa and all prisoners of conscience, and work to build common cause with the human rights movement.

Closer to home, we also need to be vigilant to the erosion of civil liberties taking place. The UK Government is planning a Public Order Bill which would further restrict the right to protest, new legislation that would restrict the ability of public bodies to boycott and divest, a vital tactic in campaigning against fossil fuels or human rights trashing activities, and to repeal the Human Rights Act.

Sign the petition to the UK Government to protect the Human Rights Act

Conclusion

It’s clear that the climate talks are not delivering for people or the planet. There were some important, hard won gains at COP27, but we know it’s not enough to turn the crisis around. At the same time the cost of living crisis, and governments’ responses to it, is hurting billions of people here in the UK and around the world.

Meanwhile corporations and governments look to keep on pumping the very fossil fuels that are destroying our one and only home, extracting maximum profit at the expense and suffering of the many.

That’s why we need to rise up together locally and globally, across movements, to demand fair climate just responses to the crises. We need to keep on fighting for the real solutions to the climate crisis and keep calling out countries and corporations for their false solutions that divert precious time and investment into fantasy techno fixes and allow – here in Scotland, and in the UN spaces.