How should we fund renewable energy in the developing world?

In conventional centralised energy systems, citizens are at best reduced to consumers who generate profits for large energy companies and their shareholders. At worst, they are forcibly removed from their land to make way for fossil fuel infrastructure development.[1]

In contrast, a decentralised renewable energy system enables ordinary people to generate and use energy locally, own or manage infrastructure and make decisions about how profit is spent. CRELUZ, a Brazilian energy co-operative started off by bulk-buying electricity from the national supplier and extending grid to previously neglected households. To combat inadequate supply they eventually invested in local generation using mini-hydro technology. Today CRELUZ supplies electricity to 20,000 families benefitting approximately 80,000 people, a quarter of which is met by local mini-hydro generation. It should also be highlighted that wealthier members of the co-operative pay relatively more to subsidise those on lower incomes, including 600 families that do not pay for electricity consumed. CRELUZ is just one of many community energy initiatives from around the world that demonstrates how energy democracy is delivering access to affordable renewables.

However, not everyone agrees on the need for citizen or community-owned energy, including those that support the transition to decentralised renewables to combat climate change or deliver energy access: “You don’t manufacture your own cars, so why make your own electricity?” a technical expert said to me recently. I am not proposing that people have to build the cars they drive or manufacture their own solar panels. But a driver can own a car, join a car club, hire a taxi or decide to ride a bicycle instead. In other words, that citizen has a choice.

Benon Bena from the Rural Electrification Agency in Uganda urges us to recognise that “a poor man will not refuse the shirt he is given.” In regard to energy, this means a community without electricity will not refuse affordable household supply from a commercial company even if it will lock the community into a twenty-year contract that drains the local economy and creates dangerous dependencies on external resources.

Instead of handing a community a one size fits all shirt, community energy is about empowering local people to create solutions that actually fit.

A bottom-up approach is also more likely to lead to holistic energy strategies that consider transport, heat, land use, women’s health as well as electricity. However, community energy models should not be imposed on people but neither should models of corporate control. As such, developing countries that are building energy infrastructure from scratch have an opportunity not just to leapfrog dirty energy technologies but also energy systems where corporate oligopolies control energy markets and drain local economies.

For community energy examples from across Europe visit www.communitypower.eu

Why global finance?

Industrialised countries have a historic carbon debt and therefore a moral obligation to support developing countries in transitioning to decentralised renewable energy systems. There is also wide recognition of the fact that basic access to modern energy services such as electricity is vital for dignified standards of living. In this context, global financing mechanisms for decentralised renewables in developing countries have been discussed for some time and are sometimes referred to as ‘globally funded Feed-in Tariff’.

There are ongoing discussions around how to use the United Nations Green Climate Fund (GCF) into which industrialised nations pledge money, to fund decentralised renewable transitions in developing countries.[2] In particular, there is excitement about a proposal by the Africa Group, a formal negotiating block in the international climate negotiations. There are also concerns that GCF money could be hijacked and controlled by corporate interests. Therefore, while supporting the Africa Group’s proposal, Friends of the Earth and others are also exploring alternative avenues for making funding from industrialised countries available. One such proposal is a Global Community Benefit Fund, a platform for voluntary financial contributions from community energy groups say in Scotland or Denmark to specific community energy initiatives in countries like Zambia or the Philippines.

The GCF and alternative funding could be used to raise funds for capital investment to deliver infrastructure developments including regional pilot schemes or to top up policy mechanisms such as national Feed-In Tariffs. Funds could also be used to build capacity at different levels including policy and community level. This may include mentoring schemes that allow communities starting out to learn from similar communities who already have a scheme up and running. REScoop, a European Initiative aimed at increasing the success of community energy schemes has already introduced mentoring schemes to support capacity building for new projects.

Delivering sufficient energy access

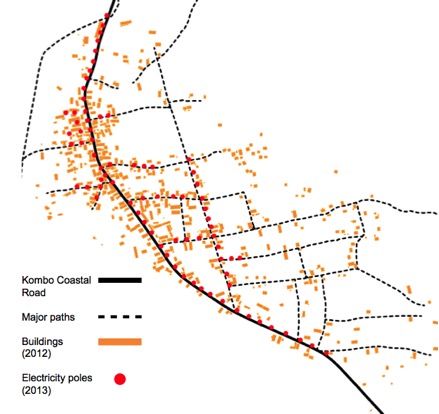

For many developing countries the priority is to deliver access to modern energy services by developing appropriate infrastructure including off-grid solutions. According to the International Energy Agency approximately 1.3 billion people are currently without access to electricity but figures on energy access can be hugely misleading. Grid electricity reached Kartong, a community in the south of The Gambia, in 2013. However a closer look at the distribution of energy infrastructure reveals that large parts of Kartong are located too far from the grid to connect, even if they manage to raise the connection fees required. Those who are connected currently face planned power cuts as the national energy supply company struggles to meet demand.

The challenge is enormous but what if we rise to it and delivering access to modern energy services to every household in the developing world? As a Westerner and therefore high-energy user, it does not feel quite right to ask those who have only recently been connected to electricity, got lights in every room or now enjoy watching television to also become energy efficient. And yet we cannot ignore energy efficiency just because it makes some of us uncomfortable. Ultimately we need to talk about energy sufficiency, both for those who need to reduce consumption as well as those whose energy use will increase for the foreseeable future but cannot follow current high consumption patterns of industrialised countries.

Anne Schiffer, Friends of the Earth Scotland

Follow @AnneSchiffer1

This article is based on seminar discussions on globally funded financing mechanisms for decentralised renewable energy transitions in developing countries hosted by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) together with the What Next? Forum in Delhi (30 March – 1st of April 2015).

[1] For example, see Marriott, J. and Minio-Paluello, M. (2012) The Oil Road: Journeys from the Caspian Sea to the city of London. London, Verso.

[2] Hällström, N. et al. (2014) Discussion Paper: Global renewable energy support programme: Globally funded payment guarantees/feed-in tariffs for electricity access through renewable sources. Uppsala, What Next Forum; New Delhi, Centre for Science and Environment.