Shell and INEOS: Oily sponsors will come home to Scotland at the World Cycling Championships

The World Cycling Championships are happening in Scotland this summer. It’s big news, not just because our wee country likes a spectacle but because it’s the first time all the different disciplines of cycling will compete together: mountain biking, track cycling, BMX and road racing. A first ever ‘olympics’ of cycling.

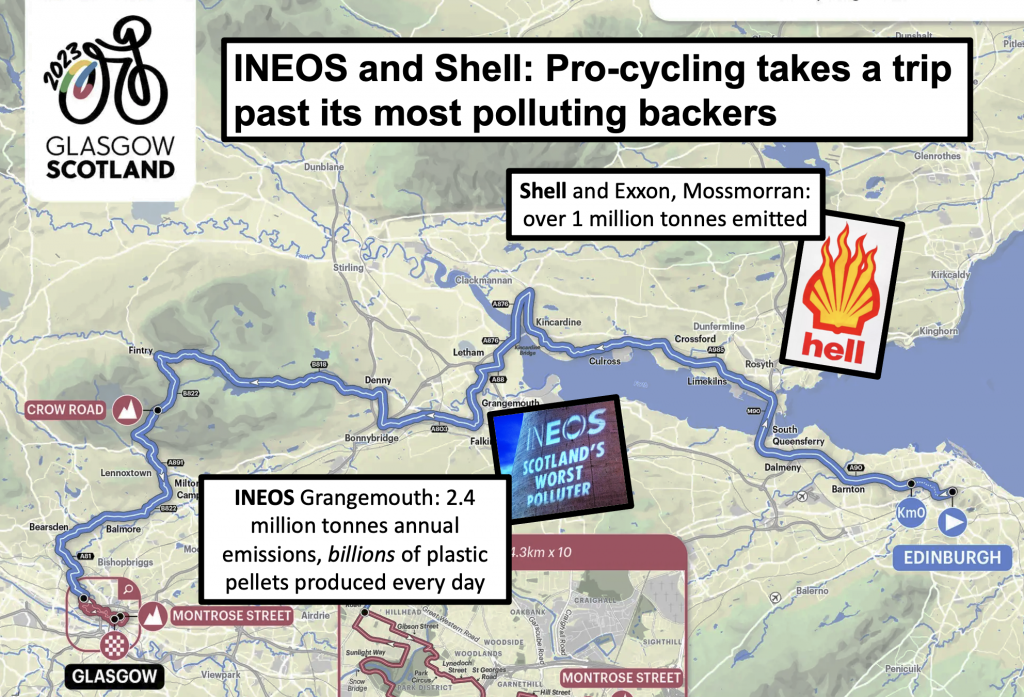

The road races will wend their way through the towns and hills of central Scotland: the women’s race starting at Loch Lomond and the men’s at the Scottish Parliament, both finishing in Glasgow – and anyone can watch the races pass on their way.

It will be a fantastic time enjoy the sport but inevitably it will also draw our attention to where it gets its money, and for men’s road cycling, that place is all too often big oil.

On Sunday 6th August the men’s road race will pass within miles of two major pollution hotspots, both owned by the sport’s biggest sponsors.

As the race leaves Edinburgh, the race will cross the River Forth and take a turn away from Fife’s biggest polluter, the Exxon and Shell-run Mossmorran gas plants, just 10 miles away.

Mossmorran, run by Exxon and Shell, is the 3rd biggest carbon polluter in Scotland at last count, and repeated lengthy flaring episodes have drawn outrage from locals in Fife.

Despite being one of the world’s biggest carbon polluters Shell, who operate half of the Mossmorran site, is lead sponsor of the British cycling team and British riders will pass this pollution zone with the Shell logo on their shoulders.

There was outrage when Shell’s sponsorship deal was announced earlier this year. Cycling News said: “the deal with Shell UK is a stain on the soul of British Cycling, as difficult to clean up as an oil spill.”

As they ride along the north shore of the Forth, the competitors may notice plumes of smoke and steam growing larger on their horizon. At Kincardine they will cross the river directly toward the smokestacks and pass just a couple of miles from Grangemouth, home to not just one, but three of Scotland’s top polluters, all of whom are owned by INEOS.

INEOS sponsor the UK-based men’s pro-cycling team, the INEOS ‘Grenadiers’ which has 11 British riders, including former Tour de France winner Geraint Thomas. Owned by billionaire Jim Ratcliffe, the company is one of Europe’s biggest plastics, fossil fuels and chemicals companies. Protests against INEOS’ sponsorship of the sport began on day 1: at the Tour de Yorkshire in 2019 there was outrage on the roadside that INEOS was using the sport to clean-up its image whilst simultaneously planning to frack for gas in Yorkshire.

The 2023 road-race will pass by the town of Grangemouth, where INEOS runs Scotland’s biggest source of carbon pollution, a huge site that includes gas power stations, an oil refinery and chemical works, importing fracked gas from Pennsylvania and producing billions of pellets daily to make single-use plastics.

Local resentment against INEOS and Jim Ratcliffe has been fuelled by decades of pollution episodes, attempts to restrict access around the site, and poor treatment of workers. Cycle protests took place when INEOS attempted to close a key local road and workers took to the streets last summer during wildcat strikes over pay and conditions. In this context climate activists have also stepped up a campaign to phase out oil production at the site. In July INEOS Grangemouth was overcome by days of consecutive rallies, blockades, invasions, and occupations by Climate Camp Scotland and This is Rigged.

Oil companies use sports like cycling to draw our attention away from the pollution they cause. At this year’s World Championships, they’ll be riding right past the very damage they’re trying to distract us from.

As they head West into Falkirk and climb the ‘Crow Road’ pass in the Campsies, riders will leave the sights and smells of Scotland’s biggest polluters behind them. But the stain of that pollution, trapped in the oil logos on their jerseys, will remain.

Scotland should be rightly proud to be hosting the Cycling World Championships and the riders will surely get a warm welcome from the crowds across the country.

We will cheer with good heart, but perhaps not with full voice. For whether it’s Team Shell or Team INEOS, few will want to cheer loudly for some of our biggest climate polluters.