What’s the problem with lithium?

Last week, we released a report called ‘Unearthing Injustice’ which looked at the harm being caused by ‘transition minerals’ – the minerals that we’ll need more of as we transition away from fossil fuels.

One of the most important minerals for us to do that is lithium.

Why do we need lithium?

Lithium is a soft, silvery metal that has been extracted commercially for over a century, with a wide range of uses. The most common today is in rechargeable batteries.

There are three main uses of lithium-ion batteries: electric vehicles, energy storage and consumer electronics, which makes it vital for the energy transition. In 2022, Scotland consumed an estimated 142 tonnes of lithium. The bulk of this consumption, 82%, went towards private cars.

Demand for lithium is growing rapidly and is expected to increase by 13 – 51 times from 2020 to 2040, depending on how rapidly decarbonisation takes place. The current global recycling rate for lithium is just 1%.

Demand is predicted to exceed supply, meaning potential shortages as soon as 2025.

What are the problems with lithium mining?

There is evidence of social and environmental impacts, including human rights abuses, connected with the lithium mining and production supplying the Scottish economy. Mining is associated with conflict because exploitation of mineral resources impacts upon nearby communities. It is an extremely energy intensive process and generates large amounts of toxic waste.

Lithium-ion batteries used in Scotland are likely to contain lithium from Chile and Australia, where there is evidence of corruption, worker exploitation and mines depleting water sources for Indigenous communities and wildlife.

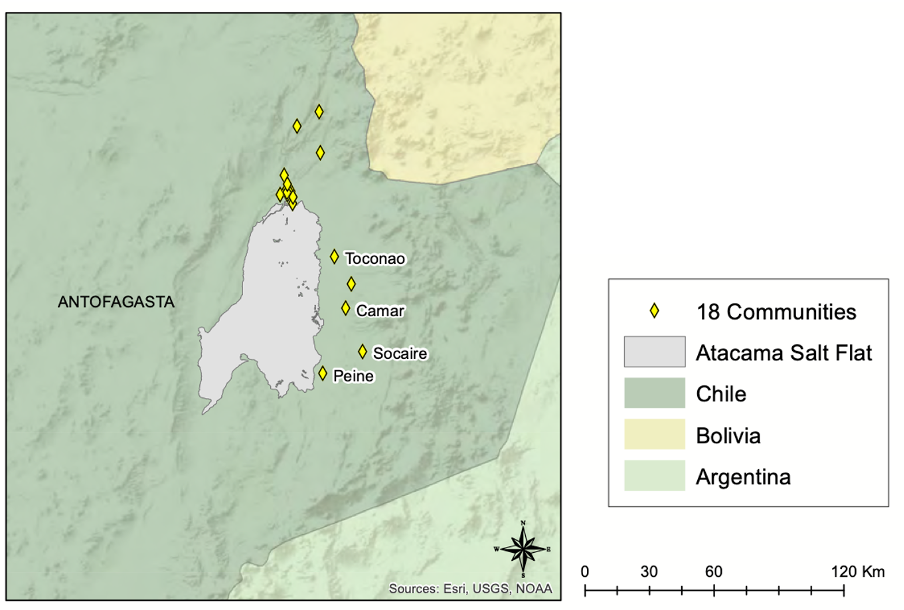

In Chile, brine evaporation, which uses vast quantities of water in an already parched environment, is one of the most significant concerns. Mining activities are said to have consumed 65% of the Salar de Atacama region’s water. The mining practices in the region mean that freshwater is less accessible to the 18 Indigenous Atacameño communities that live on the Atacama’s perimeter.

Communities have campaigned against mining companies SQM and Albemarle over unauthorised operations and inadequate environmental monitoring, using direct action tactics including road blockades and hunger strikes.

Unionised workers have also protested against exploitative working conditions. In 2021, workers settled a dispute at Albermale’s Salar de Atacama facility after opposing a contract which restricted union freedom and discriminated against the plant’s most vulnerable workers.

On the Maricunga Salt Flat, also in Chile, various companies are developing projects on the lands of the Colla People. Mining activities have disrupted their ancestral ceremonies, violating their Indigenous rights. The project developers, Minera Salar Blanco, assert they undertook a ‘lengthy process of social engagement’, but the communities say that they did not gain the consent of those affected. The nearby Sales de Maricunga project, run by a consortium of three Chilean, Taiwanese and Japanese companies, offered no consultation at all.

Large-scale depletion of salt water from the aquifers also endangers various native species, including unique wetlands where fauna and flora – including migratory birds, the Andean fox, numerous small mammals – coexist in fragile circumstances.

How can we reduce our demand for lithium?

While the impacts of mining can and should be minimised, they cannot be eliminated. Mining will always carry the risk of significant social and environmental impact. This means reducing demand will always be essential to reducing the impacts of mining.

Given Scotland’s lithium demand comes mostly from electric vehicles, and we still have a lot of work to do in reducing the climate impact of transport in Scotland, there must be a shift in how we get around. We simply cannot replace all our current petrol and diesel cars with electric cars like for like – we need better public transport, so we don’t need as many cars overall.

Replacing Scotland’s 2.5 million fossil fuel cars and 4,400 buses, like for like, would require 20,200 tonnes of lithium in total. If the proportion of journeys in Scotland taken by bus increased to 30% (which would bring the proportion of journeys made by public transport in Scotland up to the levels we see in London today) lithium requirements would be 13,800 tonnes (32% less).

We also need to stop using lithium for unnecessary purposes. Single-use vapes, which have a readily available reusable alternative, each have a lithium-ion battery. With an estimated 1.16 million bought each month and 108,000 thrown away each week across Scotland, this is enough lithium to produce around 99 electric car batteries in a year.

As well as reducing demand, better use of lithium once it enters the economy can also limit its impacts by replacing requirements for new resources. We need better reuse and recycling of lithium batteries. The batteries used in electric vehicles still retain around 80% of their capacity when they reach the end of their life, so with the right processing they can still be used for less demanding applications for many more years. There are no recycling facilities for lithium at all in the UK currently, so that would also make a big difference to the amount that needs to be mined.

We want the Scottish Government to create a resource justice strategy to ensure it’s taking into account all of these issues, and the similar ones that arise from the other minerals that will be in high demand as we transition away from fossil fuels. This must both drive supply chain due diligence, and minimise mineral demand. Transitioning away from fossil fuels is vital for a livable planet, but we must not create another crisis in doing so.