Will electricity market reform help secure the Power of Scotland?

Duncan McLaren reflects on big developments in energy matters.

Last week, the UK Government published its consultation on reforms to the electricity market to help meet carbon, cost and security goals. At the big picture levels the reforms dramatically roll back the degree of market liberalisation introduced by a previous Conservative government, but whether they will be enough to deliver virtual decarbonisation of electricity supply, affordably, while maintaining security of supply, has yet to become clear.

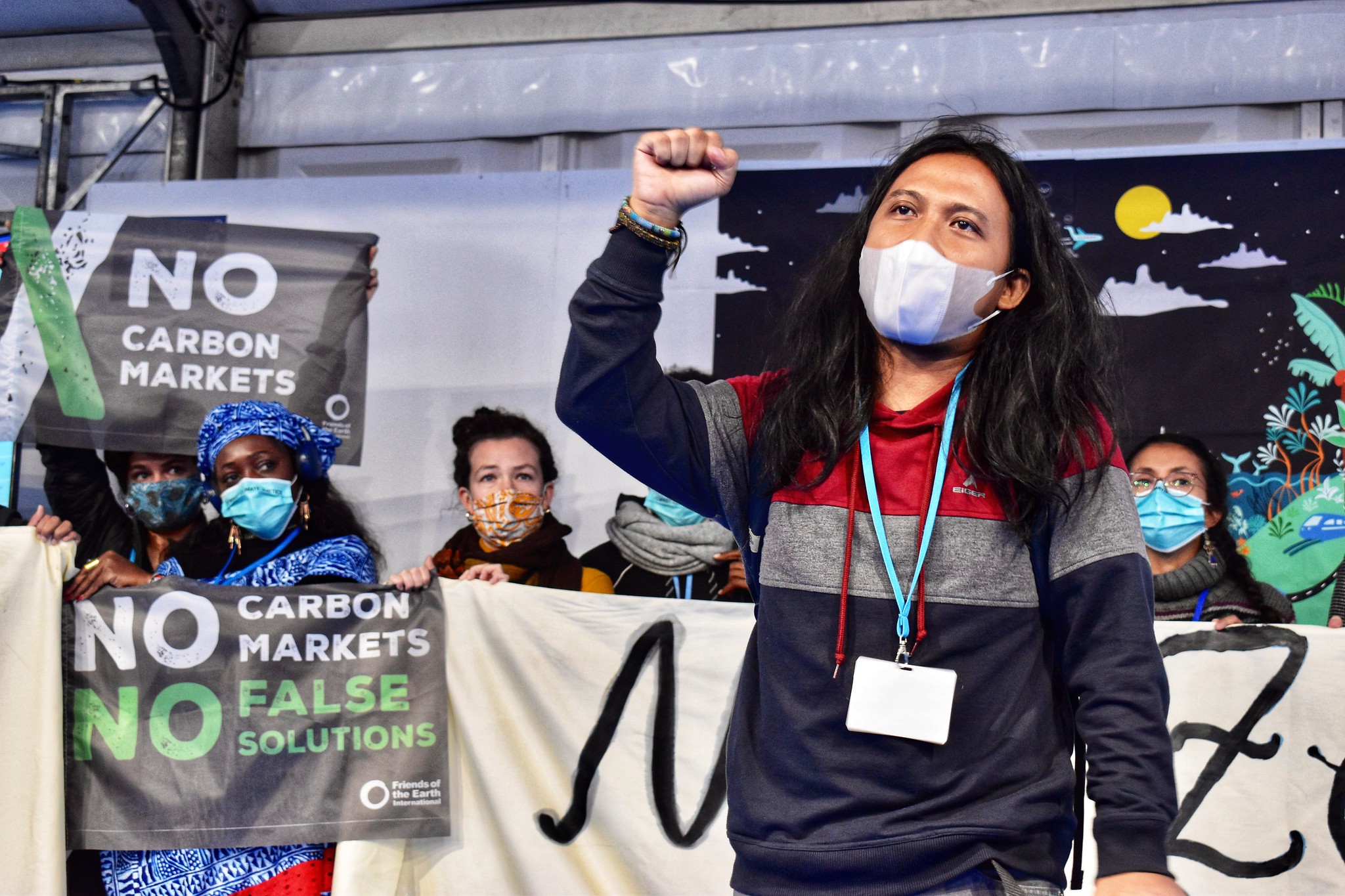

On the same day FoES published ‘the Power of Scotland Secured‘ – research showing that Scotland could deliver almost 100% decarbonisation of electricity supply by 2030 from renewables alone, without any increased risk of ‘the lights going out’, and at comparable cost to conventional approaches.

But it’s still unclear whether the Westminster Government reforms will support or hinder Scotland’s transition to a low-carbon leader based on renewable power generation. Details yet to be decided will make all the difference.

The package includes four basic measures: a sectoral carbon tax, guaranteed prices, an emissions performance standard, and payments to ensure availability of back-up generating capacity.

The de facto carbon tax for the electricity generation sector, (the so-called carbon ‘floor price’ within the carbon trading scheme) will penalise all forms of fossil fuel generation, directly proportionate to the carbon intensity of combustion. It won’t, sadly, capture embedded emissions resulting from the manufacture of equipment or processing of fuels – especially outside the UK. So the carbon intensive processes of mining and processing uranium for nuclear power will not be subject to the same carbon tax rate as the gas burnt directly in a power station.

This measure is basically sensible, although an economy wide carbon tax or price floor would be better than one restricted to power generation. That would deliver both higher tax revenues and greater emissions reductions. It would also give slightly less of an unfair benefit to nuclear power, which may be low carbon, but is in no sense sustainable. A genuinely green tax reform would include a direct nuclear tax as well as carbon taxes.

Guaranteed prices for ‘low-carbon’ electricity mean generators would receive a subsidy for the shortfall if the market price is below this level, and pay any surplus from high market prices back to the Government. This guarantee is

expected to support renewable power, carbon capture and storage, and nuclear facilities. It is not clear whether different technologies will face the same guaranteed price, or specific levels that fairly reflect the different risks involved in deployment, as there are several alternative approaches considered in the consultation.

This may prove to be an effective approach, but only if a single price is rejected. To deliver a sustainable mix of low carbon power requires discrimination. For example, higher support for emerging technologies such as wave and tidal, and support for biomass use in small scale combined heat and power, but not for large-scale biomass to electricity schemes reliant on wood imports. Technology specific prices would also allow the Government to meet its promise of no direct subsidy for nuclear by excluding it from this price guarantee or ‘feed in tariff’ mechanism.

There is even a strong case for setting different support prices in Scotland than in England. The Scottish Government has used devolved powers to vary the payments made under the current Renewables Obligation to successfully encourage greater interest in wave and tidal power. They have also used their opposition to nuclear to help provide confidence to renewable and carbon capture investors that there will be market demand for their product.

The transitionary arrangements between the Renewables Obligation and the new feed in tariffs will also be critical if investor confidence is not to stall, putting the development of supply chains for the renewables industry at risk. This is particularly critical given the apparent failure of the Government to get the Green Investment Bank up and running promptly.

An emissions performance standard (EPS) for new power stations, which would limit the amount of carbon dioxide emitted per unit of power generated. This mechanism has been used to good effect in California where the level of the EPS is set equivalent to a modern gas fired power station.

Unfortunately the proposals in the Government’s package are poor, with a suggested choice between two much weaker

levels (50% more emissions per watt, or 100% more emissions per watt than in California). The mechanism would apply only to new stations, affecting only new coal power in practice, and would never be tightened during the station’s lifespan. As a result most of the value and flexibility of the EPS approach is being jettisoned.

This also makes it less likely that the focus of carbon capture and storage (CCS) will remainon existing power stations such as Longannet and Peterhead. Combined with a feed in tariff for CCS, a weak EPS makes new coal stations more likely, despite the very high capital risks – shown by the failure of Hatfield to raise the investment needed for its pre-combustion coal CCS project.

Subsidy payments for back-up capacity are intended to ensure that either extra power can be generated, or demand reduced if renewable generation falls. So Government will pay companies to provide those services, for example by maintaining gas-fired power stations ready for use as back-up. This could also help pay for new pumped storage facilities or for deferrable demand mechanisms.

The crux will be to ensure that demand side and storage measures get a fair share of this support package. A well designed mechanism could also ensure that the introduction of electric vehicles is managed in such a way as to allow effective electricity storage in millions of dispersered vehicle batteries.

Overall the package has most of the elements needed, although they will only help deliver Scotland’s renewables investments if there are different targeted support prices which favour renewables, a tougher EPS, and confidence-boosting transitionary arrangements. Without these, at worst we will see Scotland’s renewables starved of investment in favour of new nuclear power stations in England.

But one thing would still be missing. And it’s the thing that should have come first of all – an integrated approach to demand reduction. The Government is right to assume that electrification of heat and transport will add to electricity use, but other measures can reduce electicity consumption, and reduce the overall demand for heat and transport energy, thus making the increase in demand smaller. Some of these might be delivered by the Green Deal, but in transport, Governments both south and north of the border seem determined to allow traffic to go on growing.

As the Power of Scotland Secured demonstrates clearly – getting the demand side of the picture right across the piece makes everything else easier – you need less new generation capacity, less new transmission capacity, less financial investment, and you face less risk. It’s time Governments across the UK heeded this lesson.