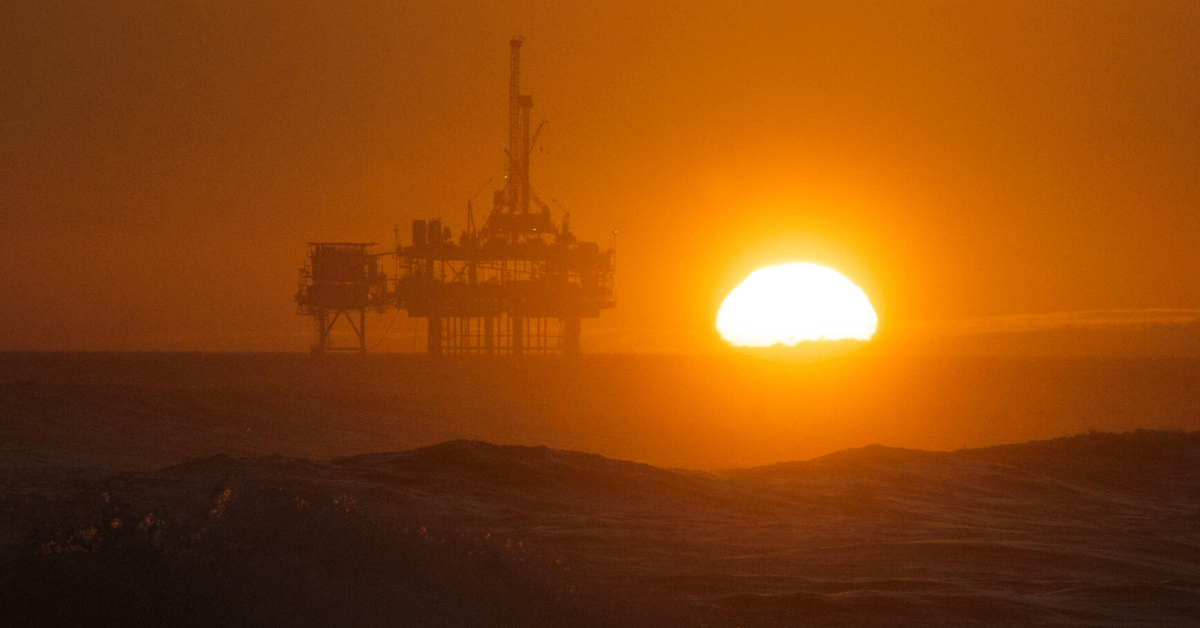

The twilight of the oil industry

Last week there was another setback for the oil and gas industry when the Swedish oil company Preem gave up on expansion plans which would have doubled the carbon emissions from their oil refinery at Lysekil, north of Gothenburg, and make it Sweden’s largest single carbon polluter.

Sweden has among the toughest climate targets in Europe, aiming to be carbon neutral by 2045, like Scotland. Our Swedish sister organisation, Jordens Vänner, has been part of the fight against the expansion plans since they were first proposed. They have been part of a long-running legal battle over the interaction of the EU’s climate emissions trading scheme and Sweden’s own climate commitments. The protest groups maintain that expanding the refinery cannot be consistent with Sweden’s obligations under the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change.

Public opposition to fossil fuels

The latest court case made a recommendation to the government that the expansion plans could proceed but the government has not made a final ruling on the plans and this could have taken several years.

Last month there was a week of action by protest groups, with Greenpeace blockading the site’s harbour, preventing an oil tanker from docking. Last year, Friends of the Earth Sweden Friends awarded Preem the Swedish Greenwash Prize.

The company said the plans were being shelved because of coronavirus, the campaigners called it a victory for people power.

The Lysekil refinery is the largest in the Nordic countries and was built in 1975. Its current annual emissions are a bit larger than the refinery at Grangemouth, which is Scotland’s second largest industrial source of climate emissions, after Peterhead power station.

The Peterhead power station is likely to shut in the next few years and the future of all the activities at Grangemouth – home to five of Scotland’s top twenty climate polluters – needs a good review. Fortunately, the Scottish Government recently announced a new body to look at the future of industries and jobs at Grangemouth, knowing that demand for petrol and diesel road fuels will plummet and there is growing pressure to drastically reduce the amount of plastic society uses.

Last week the Scottish Green Party made a call in a parliamentary debate for a similar exercise to look at the future of the controversial gas processing plant at Mossmorran in Fife. The Scottish Government response was a ‘maybe.’

Oil and gas worker dissatisfaction

There is already plenty of appetite among oil and gas workers to get out of the sector. In a further blow to the shiny image the industry likes to present a widely-reported survey of nearly 1,400 North Sea oil and gas workers found that 81% would consider leaving the oil and gas industry to work in another sector and remarkably only 7% were determined to continue working in oil and gas.

The survey, by ourselves, Greenpeace and Platform, found widespread dissatisfaction with the boom and bust nature of the oil and gas sector, and more than half of those taking part were interested in retraining to work in the renewables industry.

From cancelled projects to gloomy sales forecasts and climate change pressures the global oil industry is entering its twilight. Even its own workers are seeing the writing on the wall.

Dr Richard Dixon is Director of Friends of the Earth Scotland. A version of this article appeared in The Scotsman on Tuesday 6th October 2020.