Never too early to engage with planning

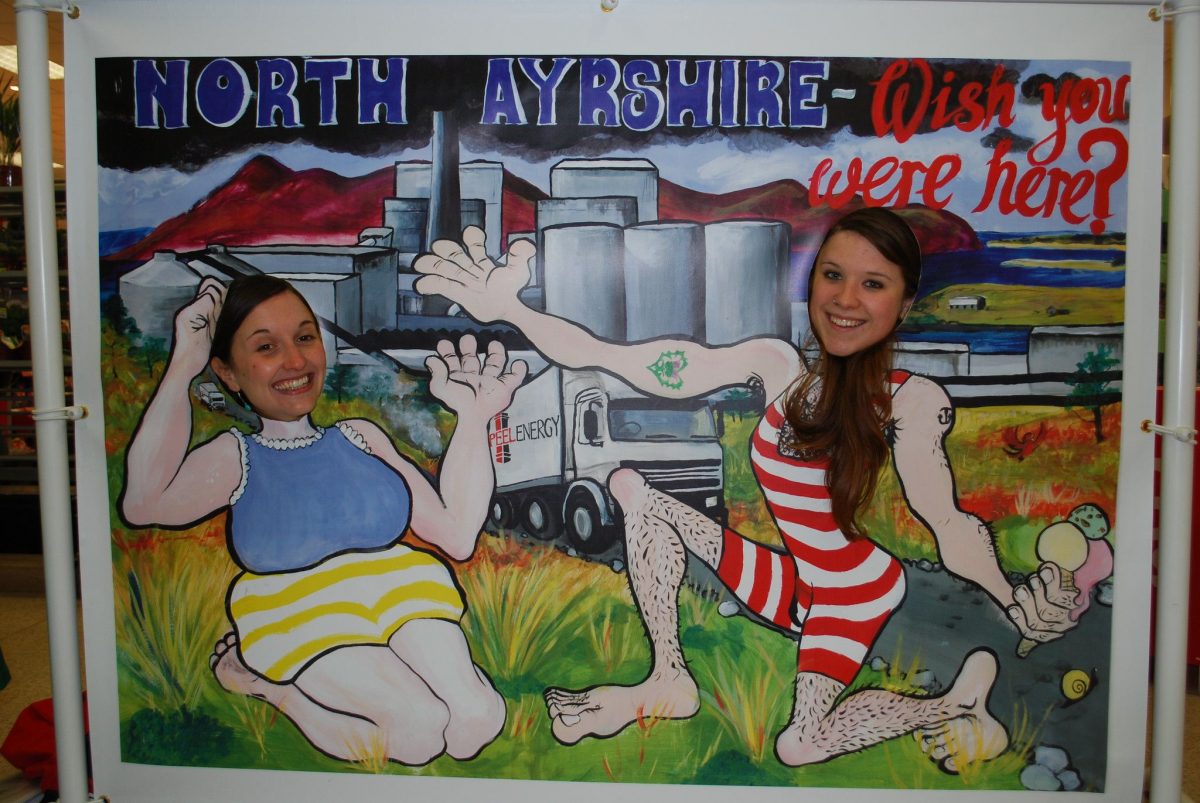

A decade ago a planning application was submitted for a large coal-fired power station at Hunterston in Ayrshire. The area already had a nuclear power station and the new proposal would take advantage of the deep-water import terminal to bring in coal from anywhere in the world.

Many local people and those concerned about climate change were appalled about the idea of a new fossil-fuelled power station. Around 14,000 people objected to the application.

An amended application attracted 22,000 objections and plans were drawn up for a Public Local Inquiry. The government reporters for the inquiry held two session for the public ahead of the formal inquiry sessions, with several hundred people turning up.

The tide was turning against fossil fuels, with the only other coal-fired power station application in the UK, at Kingsnorth in Kent, being shelved in 2009. Seeing the weight of public opinion and following a change from support to opposition by North Ayrshire Council, the developers pulled the plug in June 2012, just before the public inquiry was due to get underway.

Uphill struggle against dirty developments

One of the big surprises for the local campaigners was that they would not be able to challenge the need for a new power station. They could talk about how high the fence was supposed to be, what colour the chimney was painted and how it might affect traffic.

But they could not point out that the 2009 Climate Act required us to reduce emissions, that Scottish electricity demand was actually falling or that there was a very rapid growth in renewable electricity. They could not express their concern that the coal might come from mines with terrible condition for miners.

The inquiry would be restricted to ‘local’ issues because the idea of a new power station at Hunterston was already deemed a strategic priority for Scotland. And that’s because it was in the current National Planning Framework, the government document that sets out, among other things, infrastructure plans of national importance.

Many times local objectors have found they have an uphill struggle to oppose a development near them because that field is designated in the local council’s plan for housing, or that bit of countryside is in the National Planning Framework for a motorway.

People mostly only hear about a proposed development near them when it comes in as a planning application but the time to really try to stop something objectionable might well have been several years earlier, when one of these strategic planning documents was being put together.

Creating a new National Planning Framework

The Scottish Government has begun the process of creating the next National Planning Framework, with a deadline last week for the first set of public inputs.

Key differences this time are that the new Framework will cover policies and priorities for 10 years, up from the five years of previous versions, and the whole thing will be subject to a vote in Parliament, after next year’s Scottish election.

The National Planning Framework is a key document in shaping our nation and it can be full of things which help deliver a low-carbon Scotland or it can perpetuate our current high-carbon ways.

One of the developments which will be trying to get in will be another power station at Hunterston, this time a gas-fired one. One of the positives is that it will probably exclude any future fracking applications.

If you care about the future you should look at the proposals when they emerge later this year, to support the good things but oppose the bad, because waiting until a planning application comes in is likely to be much too late.

Dr Richard Dixon is Director of Friends of the Earth Scotland. A version of this article appeared in The Scotsman on Tuesday 5th May 2020.

View the Friends of the Earth Scotland response to the National Planning Framework call for ideas here