How people power ended the coal era

It’s September 2024 and in the countryside just outside of Nottingham, England, something momentous is taking place: the UK’s last coal power station is closing and with it ends Britain’s coal age.[1]

At the peak of its power coal employed over a million people across the UK providing energy for homes, businesses and public services.[2] Electric generation ended in Scotland in 2016, and now UK coal power is to be switched off for the final time.

Coal may now seem an anachronism, yet its demise was seldom a certainty. In fact, in 2008, Scotland was on the cusp of a new era of coal power with the First Minister Alex Salmond declaring “coal is the future”.[3]

How did such a radical change take place? What forces were mobilised in the workforce, civil society and local communities? And what lessons can we learn to guide us in winning today’s struggle for a just transition from oil and gas?

Carbon dinosaurs and carbon capture

In the mid 2000s energy giants and governments in London and Edinburgh were developing plans for a new era of coal power.

The UK generated a quarter of its electricity from coal but the UK and Scottish Governments wanted this to increase, despite warnings about increased climate pollution.

Energy companies such as Scottish Power and E.ON claimed that ‘carbon capture and storage’ (CCS) would cut pollution, but only promised plants that were ‘CCS ready’ and it was unclear what this meant. Some environmentalists believed that carbon capture could have an important role internationally but even they were unconvinced by industry claims. Friends of the Earth Scotland were already campaigning for all power plants to cut emissions, and judged that new developments were not up to scratch.[4]

In England a loose coalition of environmental campaign organisations and direct action groups committed to stopping a new coal plant at Kingsnorth in Kent. Greenpeace invaded and shut down the existing plant and painted messages on its chimneys, thousands took part in a week-long climate camp, and civil society groups held a seven-mile march to surround the plant.[5]

In Scotland coal plants at Cockenzie and Longannet were ageing, and plans were drawn up to replace them. First Minister Alex Salmond said proposals for new coal plants were “a declaration of faith in coal” and “show that coal is a fuel of the future and not the past”.

At Hunterston, Ayrshire, a new plant was proposed adjacent to an ageing nuclear plant. The Scottish Government included it in their national infrastructure plan, but this was challenged in court in Edinburgh by Marco McGinty, a local birdwatcher.

Local resistance was organised under the banner of “CONCH”: Communities Opposed to New Coal at Hunterston.[6] National backing came from conservation and environmental charities.

In 2009, in what would prove to be a pivotal moment, one of the two companies backing new coal at Hunterston pulled out.[7] Over 20,000 people filed objections to the plant and campaigners amplified opposition using the new medium of social media, forcing a public enquiry.[8]

“We may not have the same PR budget as Peel, Dong and Clydeport, but by bringing local people together we shall get our voices heard and ensure that this disastrous proposal will never go ahead.”

– Tim Cowen, CONCH

Plans for new coal at Hunterston were scrapped in June 2012, a victory for climate and nature campaigners.[9]

The ageing coal power station at Cockenzie shut in 2013 and Scotland’s largest, Longannet, closed at noon on Thursday 24th March 2016. After 46 years of operation its closure had a profound impact on the surrounding community.

Alex Pollock, who worked at Longannet for 29 years, said “there will be a lot of sadness in the community because people, local shops, local businesses, contractors have made a good livelihood at Longannet. There’s a lot of people just like ourselves who have had a good standard of living, a lot of families probably in exactly the same position.”[10]

Scottish Government minister, Fergus Ewing, said “the closure of Longannet is a mistake that will make Scotland less self-sufficient for its electricity.”[11]

However, in 2021, as part of the plant’s demolition, it was First Minister Nicola Sturgeon who pressed the button to detonate the 180m chimney stack. On its side the owners, Scottish Power, had projected the words ‘Make Coal History’.[12]

Digging in to resist opencast

In 2008 the opencast coal industry was on the advance. A new wave of mining was proposed for southern Scotland and Fife: 5.7 million tonnes of extraction, far more than in England and Wales combined.[13]

Opencast mining requires the flattening and wholescale removal of land and soil, polluting rivers and soils, creating dust and noise, damaging human health and undercutting quality of life for local people.

In Douglas, South Lanarkshire, nearly 700 out of 1,000 residents objected to a new opencast mine at Mainshill Wood, but were ignored.[14]

Coal Action Scotland formed in 2008 to take direct action against opencast and, with the community’s support, they took to the trees in June 2009 to stop this new mine.

Lindsay Addison, Co-chair of the Douglas Community Council, said of the camp: “The community is really behind it simply because there is no other thing. It is there because this is the last straw. We are all extremely pissed off. No-one wants this new mine.”[15]

Owners Scottish Coal handed the camp eviction papers on day four of the camp. With the local community’s help the activists dug in for seven months.[16]

Activists built tree houses and tunnels, blocked construction tracks and immobilised and damaged machinery. After leaving Mainshill they supported resistance at opencast sites elsewhere in Lanarkshire, Midlothian and Fife.[17] They also blockaded Scottish Coal’s main rail terminal, held climate camps, and dug ‘coal pits’ on the Earl of Home’s lawn – the landlord who was pushing through the new mine at Mainshill.

With demand for coal faltering and political support in short supply, direct action helped stem the tide of new coal and Scottish Coal went bust in April 2013, leaving in its wake a swathe of derelict mines.[18]

The Big Ask: a law for the climate

To transition a society from dependence on fossil fuels towards sustainability you need a long-term plan.

In 2007 a coalition formed to campaign for a new climate law that would require Scotland’s climate emissions to fall, with an initial goal of a 42% cut by 2020.

‘Stop Climate Chaos Scotland’ included faith groups, trade unions, national environmental and social justice organisations and local community groups. Protests and rallies took place outside the Scottish Parliament while people lobbied their MSPs inside. The campaign was bolstered by success in the UK Parliament where Friends of the Earth England, Wales and Northern Ireland led a high-profile campaign that was later adapted by other environmental groups around the world.

The coalition won cross-party support for annual targets to cut emissions. On 4th August 2009 campaigners celebrated the passing of the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009, supported by every party in the Scottish Parliament.[19]

The bill fell short on offshoring embedded emissions, a lack of carbon budgeting and accountability mechanisms, but was otherwise hailed as a major victory.

Months later, Scottish and UK leaders promoted their new climate laws at the United Nations climate talks in Copenhagen, while activists marched in Glasgow.

The Scottish Government’s long-term commitment to climate emissions cuts made proposals for new coal mining and new coal power plants look absurd, bolstering efforts for the country to transition away from fossil fuels.

Climate jobs in a crumbling economy

In 2008 the UK banking system collapsed when the unregulated gambling at the heart of the financial sector was exposed. The bank at the centre of the crisis, the Royal Bank of Scotland, was effectively nationalised.

The crisis triggered one of the worst recessions in living memory. The downward spiral also took with it green jobs, such as the Vestas wind turbine factory in England, which was then occupied by its workers, with loud support from climate activists.[20]

Whilst some activists scrambled to block new coal others began thinking about how to replace fossil fuels with something better.

Trade union climate groups launched a manifesto for ‘One Million Climate Jobs’ in 2009,[21] Friends of the Earth Scotland published a series of papers setting out how the country’s electricity could be supplied from renewables, and economic justice campaigners proposed the UK’s first ‘Green New Deal’ to fund the transformation.[22]

Community groups, many of which were organised under the ‘transition towns’ movement, got to work renewing old buildings, installing heat pumps and solar panels, such as the Edinburgh Community Solar Coop.[23] Many even fundraised to build their own wind farms and micro hydropower schemes. Energy democracy built from the ground up.

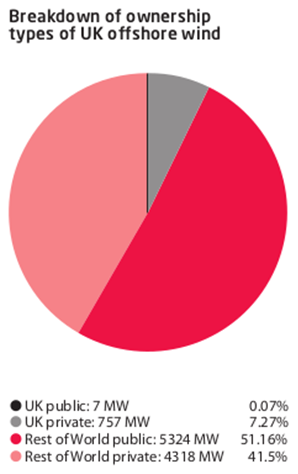

At the same time a different kind of renewables industry was on the march, its pathway paved by climate legislation and government support. Big scale and big money, big renewables extracted wealth, primarily for foreign state-owned companies.

By the time Scotland’s last coal power station shut there was no industrial policy to deliver replacement jobs in green industry. UK Government austerity saw renewables subsidies cut and construction jobs lost. Public and community ownership remained scarce.

A just transition would not be delivered at the end of the coal era. Yet lessons were learned. The experience of the end of coal showed that in order to win, we need more than just demands to end fossil fuels. Climate campaigners and trade unions need a shared vision of a better world, as well working in solidarity for the right moment in which to seize it.

Resource justice: a global struggle

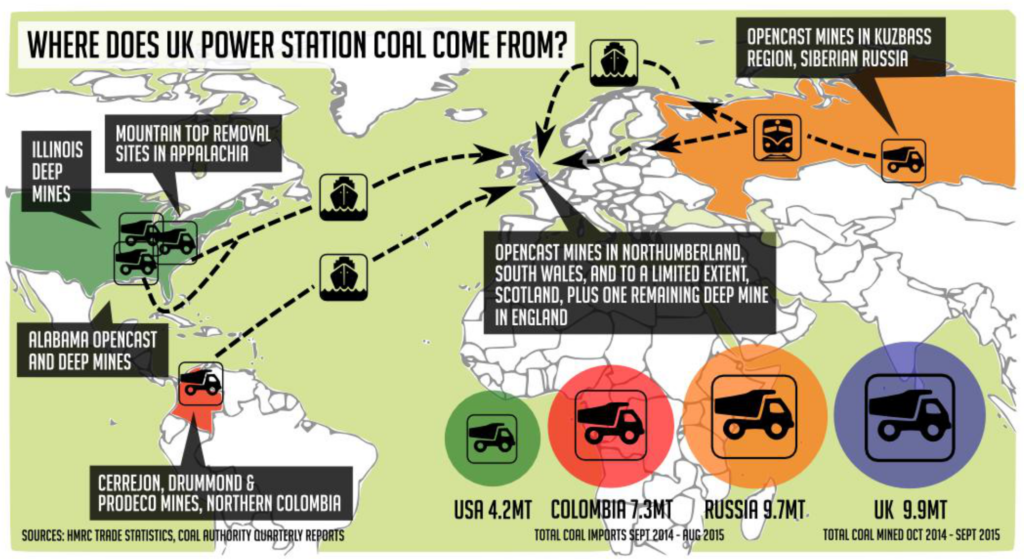

Coal is a global industry and the damage it causes has met global resistance. In 2005 global coal production surpassed six billion tonnes[24] and its burning contributed more to the climate crisis than any other industry.[25]

UK coal power plants and steel manufacturing generated demand for domestic coal but also imports. These came almost entirely from Russia, Colombia and the United States, requiring truly transatlantic resistance.[26]

In 2012 Julio Cesar Gomez came to Scotland to speak about the forced displacement of communities in La Guajira, Colombia, at the hands of coal destined for the Scottish port of Hunterston. In 2015 Samuel Arregoces, from a community displaced by this same coal, told Scottish audiences: “the mining company has privatised our water. We cannot grow on our land and the little land we have left is contaminated. We cannot live a healthy life; the water, rivers and streams and waters are polluted. We are uprooted.”[27]

Just months later, Scotland’s last coal power plant shut, and the end of our coal era saw activists’ attention turn to how Scottish money was prolonging the industry abroad.

Indonesian environmental group WALHI visited Scotland to call for divestment from BHP, who were mining the Borneo rainforest, and whose investors included the University of Edinburgh and the Scottish Parliament.

American group Keeper of the Mountains paid a visit to the Royal Bank of Scotland to demand they divest from Appalachian mountaintop removal coal. This they won, and one year later the bank was pushed to withhold cash from a major coal port project in Australia, before divesting completely from coal in 2018.[28]

Scottish students successfully pushed the University of Glasgow to become the first university in Europe to divest from fossil fuels The commitments of over 20 Scottish institutions to divest from fossil fuels have made it harder for coal corporations to open new mega mines.[29]

Growth in global coal extraction has now stalled and at COP26 in Glasgow, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson claimed an agreement to phase down coal “sounded the death knell for coal power”.[30]

Scotland’s historic transition from coal to wind power has cut climate emissions but instead of importing exploitatively mined coal we are now reliant on imported lithium and steel creating new networks of exploitation. If Scotland is to develop a truly just energy economy, it will need to build new global networks of solidarity.

Finding a just transition

‘New coal’, branded essential by politicians and captains of industry, was defeated by the actions of a loose and largely accidental coalition of groups wielding direct action, civil disobedience, and sabotage, but also letter writing, lobbying, marches, media work and a lot of patient and dedicated community organising.

Since the coal came from Scottish opencasts as well as Colombia, the USA and Russia, new networks of solidarity were built that led to divestment depriving the industry of cash.

There were important victories, but there would be no just transition from coal. Some coal pits were dug, others were defeated, and still more became derelict: the end of a story of decline that dated back to Thatcher’s attack on deep coal, and before.

Community and privately-owned renewables were built. New coal power was halted but replacement jobs constructing wind farms, home insulation and public transport failed to appear as a result of UK austerity and a lack of industrial policy.

Energy firms lost credibility as their claims of capturing carbon were ultimately ignored but they did not lose their hold over our energy system which remains in private hands.

The story of coal’s demise shows clearly how social movements can reshape our world. The banking crisis and austerity blocked pathways to wider change, but campaigners still found ways to win, riding a wave of public concern about the climate crisis to reshape Scotland’s energy system. We are given glimpses of how, in the face of daunting odds, we might achieve future victories which bring about not only transformation, but justice as well.

This story was produced as an exhibition with accompanying videos and photos: please contact Friends of the Earth Scotland for information.

Written and produced by Ric Lander, Friends of the Earth Scotland, with thanks to Oli Munion, formerly of Coal Action Scotland, Anne Harris, Coal Action Network, Richard Dixon, formerly of WWF Scotland/FoES, Zoe Clelland, RSBP, Aedan Smith, RSPB, and Richard Solly formerly of the London Mining Network.

[1] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c886qd2g80xo

[2] https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/historical-coal-data-coal-production-availability-and-consumption

[3] http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/scotland/7487184.stm

[4] https://foe.scot/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/dinos.pdf

[5] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2009/jul/03/kingsnorth-power-station-humanchain-protest

[6] https://web.archive.org/web/20130213054015/http://www.conchcampaign.org/

[7] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2009/oct/12/dong-energy-coal-plant

[8] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-glasgow-west-15663764

[9] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-scotland-business-18602532

[10] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-edinburgh-east-fife-35882883

[11] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/mar/23/longannet-power-station-to-shut-next-year

[12] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-edinburgh-east-fife-59578148

[13] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2009/aug/14/coal-energy

[14] https://www.dailyrecord.co.uk/news/local-news/opencast-plan-approved-despite-major-2440661

[15] Sunday Herald, 9th August 2009, p.10, ‘A climate of fear’

[16] https://climateactionscotland.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/mainshillzineweb.pdf

[17] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-edinburgh-east-fife-11535637

[18] https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/13135416.councils-left-200m-shortfall-funds-clean-opencast-mines/

[19] http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/scotland/8115597.stm

[20] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2009/jul/21/wind-turbine-factory-occupation

[21] http://www.campaigncc.org/sites/data/files/Docs/one_million_climate_jobs_2014.pdf

[22] https://greennewdealgroup.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/a-green-new-deal.pdf

[23] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-edinburgh-east-fife-34391241

[24] https://www.iea.org/energy-system/fossil-fuels/coal

[25] https://www.iea.org/reports/co2-emissions-in-2022

[26] https://www.coalaction.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Ditch-Coal-Report-2016.pdf

[27] https://foe.scot/where-your-money-goes-the-toxic-toll-of-bhp-billiton-in-borneo-and-colombia/

[28] https://foe.scot/royal-bank-scotland-10-years-climate-campaigning/

[29] https://foe.scot/campaign-stories-looking-back-at-glasgow-universitys-fossil-free-first/